The southern Indiana fields are an unlikely proving ground for BP Plc’s $4.1 billion bet on renewable natural gas.

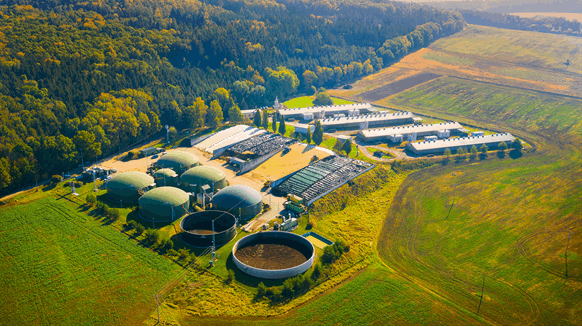

There, in the small rural town of Medora, a first-of-its-kind modular facility will begin operating on Wednesday, turning waste gas released from decomposing garbage at the area’s landfill into a product ready for pipe BP hopes the facilities are the start of things to come: The company has five more modular facilities on track to come online this year and plans to bring up to 20 into service across the country annually

The work will bring both environmental and economic benefits by keeping a powerful greenhouse gas out of the atmosphere and selling it as an energy source, said Starlee Sykes, CEO of Archaea Energy, the RNG producer that BP bought last year.

“Instead of letting it go into the atmosphere and create odors for communities, we’re going to capture that gas, refine it and sell it back into the pipeline,” he said. “Our aim is to make a large and material business that is a strong profit center for BP.”

The facility represents the next phase of the British oil giant’s push into RNG, as the company looks to leverage Archaea’s modular designs to quickly roll out facilities in the United States. The plants, usually pre-built in Pennsylvania, can be installed in nine months instead of the 18 to 24 months it usually takes to build them on-site.

Conservationists have warned that renewable natural gas is far from a long-term solution to combating climate change, as the product is still a greenhouse gas, and an especially potent one, pound for pound at least 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide to heating. the atmosphere for the first 20 years after its publication. And when burned to produce electricity or heat, landfill-collected methane produces carbon dioxide just like its fossil-based cousin.

The Medora plant is being activated amid growing interest in RNG, which is increasingly valued not only for helping oil companies reduce the carbon intensity of their products and achieve net zero goals, but also for their economic benefits . GNR, converted from the mixture of methane, carbon dioxide and other materials that come out of cow manure on farms and garbage in landfills, is chemically no different from conventional natural gas. This means it can be transported in pipelines, compressed to power trucks or burned to generate electricity.

And while it’s generally more expensive to produce than fossil-based methane, GNR producers can take advantage of a number of incentives, including credits under California’s low-carbon fuel standard and the federal fuel standard renewable that forces the use of alternatives beyond gasoline and diesel. . An alternative fuel tax credit worth 50 cents per gallon and an investment tax credit that was expanded in last year’s climate law, which can be worth up to 50 percent of project costs, can provide additional support.

Incentives are helping drive the oil industry’s adoption of renewable natural gas. Last November, Shell Plc said it was buying Nature Energy Biogas A/S for nearly $2 billion, an acquisition that would make Shell Europe’s largest producer of RNG. Chevron Corp. has worked with Brightmark LLC to produce lactic biomethane to fuel long-haul trucks.

Some environmentalists argue that it is a false solution. Burning methane from landfills and manure ponds to produce energy is better for the climate than letting it escape unrestricted into the atmosphere. But some of that methane will still leak from processing equipment and pipelines. Moreover, critics argue, relatively small amounts of GNR are collected at each site, even as the operations effectively prolong the world’s dependence on natural gas.

But U.S. policymakers have weighed moves that could expand RNG’s value, including a plan that would award Renewable Fuel Standard credits for using electricity generated from the gas to charge electric vehicles.

BP aims to increase biogas supply volumes roughly sixfold by the end of the decade, to around 70,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day. The modular system deployed at Medora is key to this trajectory. With every minute that passes at the Medora plant, about 3,200 cubic feet of landfill gas will be processed, with nitrogen and carbon dioxide removed and burned. Ultimately, about 1,000 cubic feet of renewable natural gas will be produced every 60 seconds and sent into pipelines. That’s just a small fraction of BP’s total natural gas production, roughly 6.8 billion cubic feet per day worldwide, according to Bloomberg data. BP’s Archaea has another 80 projects waiting behind it.

–With assistance from Kevin Crowley.

To contact the author of this story:

Jennifer A Dlouhy in Washington at jdlouhy1@bloomberg.net