As this brutally hot summer creeps into Labor Day, we’re all dealing with rising gas prices as we hit the beach, barbecues, or the mall for back-to-school shopping. Crude production cuts by the Russians and Saudis are the main culprit, and the situation would probably be much more precarious if it weren’t for strong US shale production that keeps gas prices from rising to 5 dollars a gallon or more, except in California of course. It is crucial to maintain this long-term production not only to replenish US oil reserves but to grow them. In today’s RBN blog, we continue our look at crude oil and natural gas reserves with an analysis of the critical issue of reserve replacement by major oil-focused US producers.

At Say You’ll Be There, we posed the question, “How much longer can US shale reserves support growth in US oil and gas production?” EIA estimates of “proved” reserves, which are assumed to have at least a 90% chance of eventual recovery under existing economic and operating conditions, imply about 10 years of remaining volumes of crude oil and condensates and 10 to 17 years of natural gas. the main producing basins. The rate at which US producers replace the reserves they use through production is critical to maintaining or improving these inventories. Equally critical (especially in an era of greater scrutiny of capital efficiency) is the price paid to achieve this rate.

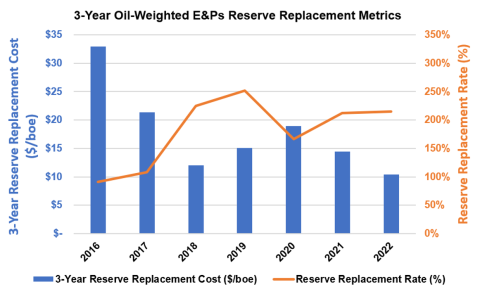

In the previous delivery In the reserve replacement series we continue today, we looked at the overall reserve replacement metrics for the top 41 US E&Ps we monitor. Using three-year averages, the most reliable method for analyzing long-term trends, we found that the reserve replacement rate recovered from a significant drop in 2020, when falling prices led to revisions massive negative reserves, up to a much healthier 200. % by 2022. This doubling of added reserves was achieved at an average reserve replacement cost of just under $10 per barrel of oil equivalent (boe), compared to nearly $25/boe in 2016 and 15 dollars/boe in 2020. These results were achieved. with a reinvestment rate (total cash flow divided by capital expenditure) of 39%, minimum in 10 years. That pushed the average recycling ratio, a measure of profitability calculated by dividing the net profit per boe by the cost of finding and developing a barrel, to the 500% range in 2021 and 2022, again a record performance. While these metrics suggest a healthy industry, we did find some cause for concern. On the one hand, we found that the percentage of reserves replaced through research and development activities has been decreasing, while the cost of operating existing fields and developing new fields has been increasing. Factors include the low rate of reinvestment and inflation in oilfield service costs. Producers have been turning to purchases to shore up reserves, but this tactic does not add to total US reserves and potential targets are limited.

Today, in Part 2, we focus on the largest oil-weighted producers, whose performance is most crucial to addressing the important issue of the longevity of U.S. shale production. As shown in Figure 1 below, the onset of the pandemic in early 2020 had a less dramatic impact on reserve replacement metrics for oil-weighted E&Ps than the severe drop in oil prices in 2014- 15 (for this chart, the three-year period in question ended in 2016: the blue bar on the far left and the far left of the orange line). The impact of the industry’s shift to the much more productive unconventional shale resources caused reserve replacement costs (blue bars, left axis) to fall from more than $30/boe in 2016 to about a third of that cost in 2018. Replacement costs increased in 2020 as negative reserve revisions (linked to the sharp drop in crude oil prices) offset reserve additions. Producers reduced capital expenditures but maintained reserve additions, resulting in a decade-low three-year reserve replacement cost of $10.29/boe (blue bar in extreme right).

Figure 1. Oil-weighted E&P 3-year reserve replacement metrics. Source: Oil & Gas Financial Analytics, LLC