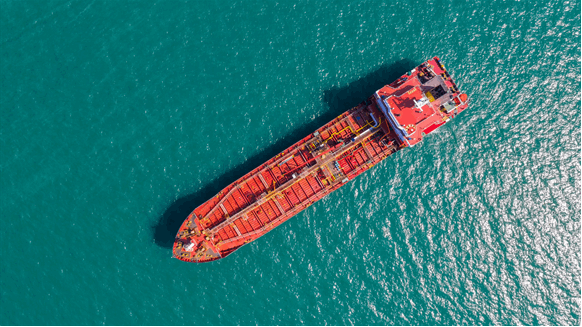

An armada of tankers carrying sanctioned oil around the world is getting younger, bucking a months-long trend of using the world’s oldest and most dangerous ships.

Shortly after President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine early last year, hundreds of aging tankers were snapped up by a cohort of faceless traders, middlemen and investors to keep Russian oil flowing. By some estimates, the purchases, in addition to ships already carrying crude for Venezuela and Iran, created a dark fleet of more than 900 people.

Now, the average age of ships being bought is declining, according to data from VesselsValue Ltd., a shipping deals researcher. Two industry executives said the crackdown in Asia was likely a catalyst for the change, following a series of arrests in recent months over security concerns.

China, a major consumer of Russian and Iranian oil, recently increased controls on older tankers at the key port of Qingdao, forcing some to wait more than a month to unload their cargo. Anxiety over aging ships was heightened when a 26-year-old ship exploded off Malaysia in May.

Singapore has also detained tankers for failing safety inspections at a record clip in recent months. The newer vessels, as long as they are well maintained, should help allay some importers’ fears about their seaworthiness, although the fleet remains awash with vintage vessels.

“Safety concerns around older vessels is one of the reasons why buyers are opting for newer vessels,” said Rebecca Galanopoulos Jones, senior analyst at VesselsValue.

According to VesselsValue, the average age of tankers sold to undisclosed buyers, a defining characteristic of a ship that is part of the dark fleet, fell to 15 years. As recently as October, it was 19 years ago.

Delay in demolition

The characteristics of Dark Fleet tankers vary. Often, however, they are older vessels without industry-standard insurance or other Western services, and owners difficult to track down. The ships are close to or over 20, an age when ships are usually scrapped.

Some countries take a hard view of older ships. In addition to Chinese controls, India banned ships over 25 years old from entering its ports earlier this year.

“Some shipowners are more comfortable handling restricted crude, such as Russian flows, as they see this trade as here to stay,” said Anoop Singh, global head of shipping research at Oil Brokerage Ltd . “Now they’re more willing to do that. invest in younger ships that will meet broader industry standards for longer.”

When buying for the Russian trade first came about, it made sense to buy the oldest ships available. These vessels are the cheapest and operating without Western services allowed them to avoid many of the current sanctions on oil exports, including a $60-a-barrel price cap on Russian crude that was imposed by the Group of Seven.

The increased demand for ships has extended the useful life of many. Not a single large tanker has been scrapped for seven months, something that hasn’t happened since at least the mid-1970s, according to Clarkson Research Services Ltd., a unit of the world’s largest ship broker.

Tankers also spend more time in transit. The pool of buyers for Russian crude has shrunk since the war, meaning cargoes that used to take a couple of days in the Baltic Sea now travel for weeks to reach China and India.

That has pushed benchmark earnings for oil tankers to about $100,000 a day twice since the war broke out, compared with an average of $23,000 a day since 2017. More purchases of younger vessels raise the chances that the rates return to the highest level as you lower the level. supply of ships for conventional trades.

There is a strong safety rationale for moving to newer ships. In May, during an inspection in China, an aging tanker was found to have more than 20 defects. And many of the older tankers that can serve the trade have already been acquired.

“The pot of old bangs is drying up, so it’s a natural progression to take newer vessels,” said Halvor Ellefsen, tanker broker at Fearnleys Shipbrokers UK Ltd. also a more certain supply of oil from the sanctioned countries”.

–With assistance from Ann Koh, Elizabeth Low, Sharon Cho and Alaric Nightingale.