Europe rushed to secure liquefied natural gas in an effort to ease a crippling energy crisis. Now, there is a possibility that his plans to build more import terminals for the fuel have gone too far.

From France to Poland, the region is looking to build LNG infrastructure after Russia severely cut pipeline supplies following its invasion of Ukraine. But this capacity could significantly outpace demand for the fuel after 2030 as countries increasingly embrace renewable energy.

If all the planned terminals are built, there is a risk that billions of euros in infrastructure will become long-term stranded assets.

“Some of the investment in LNG import infrastructure was made by the markets based on the assumption that there will always be demand somewhere in Europe,” said Ogan Kose, managing director of gas specialist Accenture Plc natural “However, if each country seeks to have its own import capacity and the markets will not work collaboratively, then of course there will be a lot of sunk costs.”

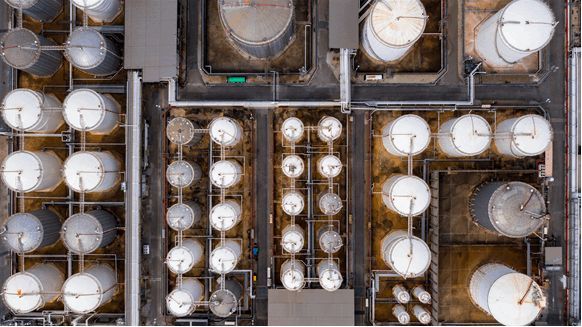

At the moment, new LNG terminals are appearing in several countries, with the energy crisis still in focus. Italy is about to start its fourth installation. Germany is pushing to deploy its fourth floating terminal off the Baltic island of Ruegen. These structures are often preferred as they are cheaper and faster to build than ground ones. Other projects are planned in countries such as Estonia and Greece.

Europe’s LNG import capacity is expected to increase by around 50% this decade, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. Meanwhile, some scenarios suggest that LNG demand will not increase, and could even fall. By 2030, the European Union could have as much as 250 billion cubic meters of unused capacity, more than half of the bloc’s total gas demand in 2021, the researcher said in a March report.

Short term demand

Europe survived the crisis last winter without any major supply disruptions due to unusually mild weather, lower energy consumption and an influx of LNG. As a result, gas storage levels are now well above normal for the time of year.

Still, ships are carrying record levels of LNG to the continent as the risks of next winter loom. On peak days, existing facilities have been operating at full capacity, leaving LNG tanks idling at sea waiting to unload their cargoes.

For now, Europe has no choice but to build new infrastructure to meet the current demand for LNG. Terminals are not built to operate at full capacity year-round, and it is common for them to have an average annual utilization rate of 50% to 70%, or even less.

The region could add two to four more floating terminals than those already being planned, said Thomas Thorkildsen, chief commercial officer of Hoegh LNG, which has supplied Germany with two such units for 10 years.

“We see a lot of interest in more capacity in several countries in northwestern Europe,” he said in an interview. “However, there are opposing views, and political processes and decisions must be concluded before commitments are made.”

Long-term risk

The concern is the lack of long-term demand. The European Union could cut its gas use by almost 45% by 2030 as it moves towards renewable energy sources, under a scenario predicted by the International Energy Agency.

The capacity of some of the existing terminals in Europe is certainly reserved until 2045 or even 2050, according to Elengy SA, which operates three land terminals in France and had an average utilization rate of 95% l ‘last year.

The EU sees the additional capacity as a buffer to provide energy security. In addition, floating storage units can function as LNG carriers if demand for capacity fades. They may also move to other locations, such as growth markets in Asia. Some new terminals could be converted for use with other products such as ammonia or hydrogen.

Europe will still need LNG in 2030 and even beyond, said Esther Ang, head of LNG at Swiss trader MET International AG. More export projects, from the United States to Qatar, will add more supply to fill the markets.

“There are more LNG projects in the world now than in the past,” he said in a recent interview in Amsterdam. “There will be times when these assets will definitely be needed and times with potentially less demand, but it’s about managing that risk.”

–With the assistance of Elena Mazneva.