Some things rob your engine of its performance. Dirty air, dirty fuel and air leaks can limit your engine’s potential. Not all engine enemies are performance thieves. Sometimes the target is engine parts.

Internal and external parts can be adversely affected by corrosion. In the air stream, we see corrosion or sulphurization at high temperature, as it is known. We see corrosion on the compressor parts. Right now, I want to focus on two components: the air intake box we discussed earlier and the rear reduction gearbox housing.

When air enters the engine, it flows through the intake box. This causes discomfort to the inbox coatings. If there is any material in the air, it acts as a blasting medium and can use the casing coatings. Even high velocity water, the air entering the inlet box can be abrasive. The engine maintenance manual contains very specific inspection and repair criteria. Even if you lose the coating and start to get some corrosion, there are steps you can take to protect your part and take care of it during the next maintenance/overhaul time.

I started thinking about corrosion because of some issues we’ve seen with the rear reduction gearbox housing. This is an area of the engine that you cannot visually inspect. It’s hard to determine if you have a problem until it’s too late. What is the problem and what can we do? I’m glad you asked.

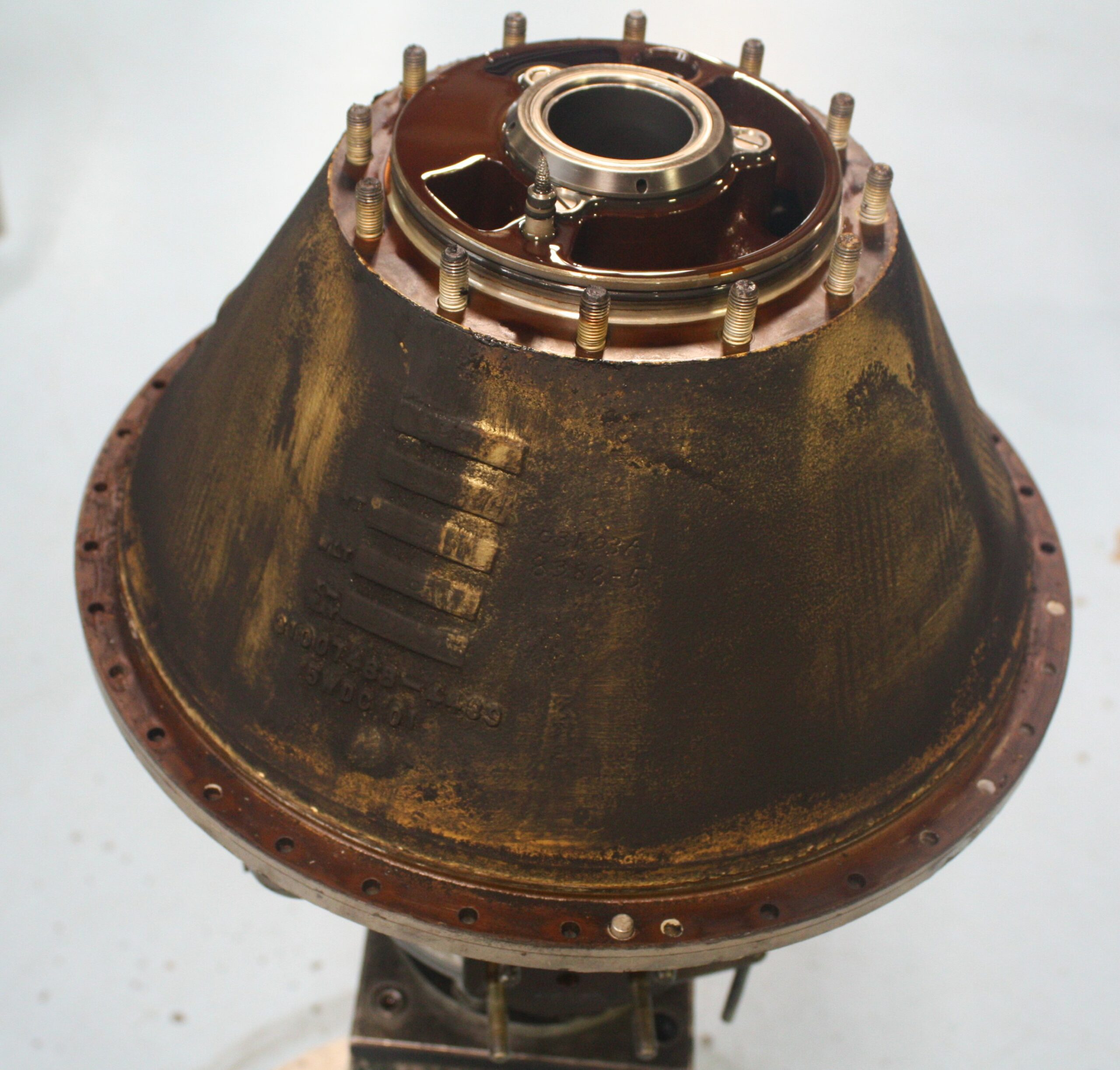

The RGB back shell is a coated part. The base material is treated, a surface sealer is applied, and finally a two-part aluminized epoxy primer and coating is applied. If you’ve been around PT6 for a long time, you may remember the previous version of the surface sealer. The coating used to be varnish. You may remember oil varnish flakes. It was a real problem. The new coating is a much harder substance and is a significant improvement over varnish. All this protection, and we still see problems.

When we do a disassembly of the power section, we visually get a chance to see the outside of the RGB rear housing. There is a gap between the power section exhaust duct and the RGB rear housing. Most of the void is occupied by an insulating blanket. This barrier is essential as it protects the oil contained in the power turbine and the RGB rear housing from the temperature of the hot gases exhausting the engine. However, there is a small pocket at the end of the insulation blanket that would allow moisture to hold in and corrosion to form.

There can be several contributing factors to the root cause of corrosion problems. There is usually a lot of carbon build-up in this area. Carbon is potentially generated from the rotor and stator air seals of the motor. A small amount of oil gets past the air seals and then burns off when the engine is hot. This carbon could contain moisture in this area. There are also three different materials; the casing, the exhaust duct and the insulating blanket. This gives us the different metal or galvanic corrosion potential. When two dissimilar metals come into contact, one of the metals undergoes galvanic corrosion. This process also requires the presence of an electrolyte. The electrolyte can be moisture, dirt or oil, which we have already established in this area. This is where I think the problem comes from.

What can you do to give your RGB housing a chance? Pratt and Whitney Canada tells us first to make sure we give every opportunity to protect the engine from moisture. When the engine is idle, we put desiccant bags in the exhaust to remove moisture. When we perform an engine flush or flush, we ensure that the exhaust duct drain is free of carbon and that the water flows freely. After washing, we also run the engine enough to raise the temperature to dry out any possible moisture. Here are the immediate things you can do to give yourself the best chance of protecting your share.

Air seals are the other part of this equation. If your power section hasn’t been inspected in many hours, or if you’re continuously running from less-than-smooth strips, it may be time to consider an inspection. Do you want to just ignore it? We recently heard from a pilot a few miles from landing and noticed a steady decrease in oil pressure. Upon landing, the oil pressure reached zero PSI. Further inspection of the engine revealed that its housing had a hole, which allowed the engine oil to leak out. This is the worst case scenario. Many casings we find on inspection have corrosion beyond repairable limits, and we just have to replace them. I just wanted to share what could happen.

Be aware of your engine’s enemies. Follow best practices. Consult your maintenance manual. Listen to your engine. I like to remind everyone that the PT6 will let you know when it has a problem.

Robert Craymer has worked on PT6A engines and PT6A-powered aircraft for the past three decades, including the past 25 years at Covington Aircraft. As an A&P licensed mechanic, Robert has held every job in an engine overhaul shop and has been an instructor for PT6A maintenance and familiarization courses for pilots and mechanics. Robert has been elected to the NAAA board as a member of the Allied Propulsion Board. Robert can be reached at robertc@covingtonaircraft.com or 662-910-9899. Visit us at covingtonaircraft.com.