SALT LAKE CITY – At the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America at the famous Daytona Speedway in Daytona Beach, Florida, a new name printed on a plaque now hangs on the wall.

A display set up just a week ago dedicated to this same person is surrounded by glass, celebrating his well-deserved induction into the hall of fame.

It’s a name that many who visit the museum may never have heard of, considering it rose to fame a century ago. But for many in Utah, the name might ring a bell, and if it doesn’t, maybe the vehicle he drove will: Ab Jenkins and the Mormon Meteor III.

And if none of this sounds familiar, Jim Williams will be the first to explain why it should. Ab, he said, was the man responsible for making the Bonneville Salt Flats famous.

“The story of what happened in the salt flats with auto racing was very important. It’s all over the world,” he said.

It wouldn’t be the global bucket list destination it is today, he explained, if it weren’t for Ab Jenkins.

Williams is the curator of a different museum 2,300 miles away from the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America museum, caring for perfectly preserved and restored cars dating back to the early 20th century.

The cars make up the fascinating collection at Salt Lake City’s Price Museum of Speed. Williams is passionate as he explains why each vehicle is important, unique and cool.

“This is history. This is automotive history here,” Williams said. “Each of these cars has a story and has made the world a better place for cars.”

He loves telling people the story behind the beautifully restored orange and blue 1930s Duesenberg that sits in the middle of the room all by itself.

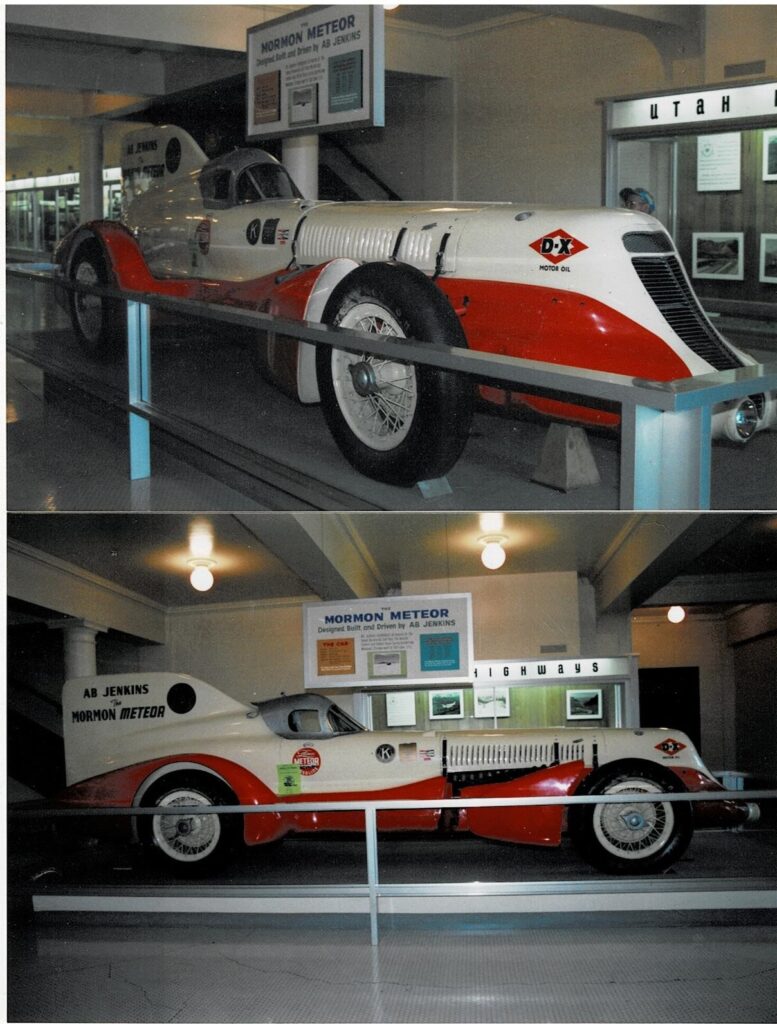

The Mormon Meteor III may be 85 years old, but it looks like it was just built.

“It’s probably the most important car in Utah; it has a lot of Utah history,” Williams explained. “He set a lot of speed records that still stand [in place] today.”

Williams undid the brown leather straps to lift one side of the hood, revealing an impressive, monstrous engine with 12 exhaust pipes extending artistically from the side in a wave shape.

“It’s a Curtiss Conqueror airplane engine. It’s 1570 cubic inches. That’s big,” Williams said with a laugh.

But the engine isn’t what makes the machine so great. Ab Jenkins, the man who drove it, made that race car famous.

“To me, he was one of the superstars of the sport,” Williams said.

The Mormon Meteor III (KSL TV)

Born in 1883 in Spanish Fork, Ab originally worked as a builder and, as his grandson Ab Jenkins II recounted, would time his commute between jobs.

Jenkins II explained how Ab would enter a Western Union, take off to his destination and then enter the next stop.

“He found a way to drive a car from this place to that place, and he just wanted to do it faster and faster and faster,” Jenkins II said. “And recognition came naturally.”

Jenkins II, who is named after his grandfather, described how Ab made a name for himself, to the point that Ab was hired full-time by the automaker Studebaker.

It was only natural for the fast rider to become a racer.

In the 1920s, Ab’s fame grew when he performed long-distance stunts, such as racing his Studebaker against a Union Pacific train from Salt Lake City to Wendover and New York City in San Francisco.

He won, of course, both times.

According to a photo of Ab standing next to his Studebaker, he completed the 3,471-mile cross-country trip in 86 hours and 20 minutes.

“He had a lot of stamina,” Jenkins II said. “It was amazing.”

Ab Jenkins stands between two Studebakers (Courtesy: Documentary Boys of Bonneville)

Ab’s favorite place to push the limits was at home on the Bonneville Salt Flats, racing against time rather than against others.

“The salt flats was something he loved,” Jenkins II said. “And he felt in his own heart and mind that that was the place for people to come and compete.”

Jenkins II said Ab promoted the Bonneville Salt Flats, recruiting racers from all over to come out and try it.

“He’s the one who convinced all the European riders to come to the salt,” Williams said.

Williams explained that at the time, Daytona Beach was the popular place to race, but the hot sand often destroyed tires and led to fatal crashes.

The salt was much cooler and didn’t destroy the tires, Williams said, creating better and safer conditions for racing.

Because the Bonneville salt flats are unpopulated, Williams said crews would set up tent cities on the salt. They had to bring everything to support the races, often redesigning and rebuilding vehicles on the fly.

In the 1930s, Ab began racing a Duesenberg that was named the Mormon Meteor, after Williams said the Deseret News held a contest and three people submitted the same name.

The three contest winners split the $25 prize three ways, which Williams noted was a good chunk of change in 1934.

Jenkins II said his grandfather was a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Ab’s faith drove him in the way he lived his life. He described how his grandfather refused to advertise for liquor or tobacco companies because he did not want to influence young people that way.

Ab Jenkins takes off in the Mormon Meteor III at the Bonneville Salt Flats (Courtesy: Boys of Bonneville documentary)

The Mormon Meteor I would be transformed into the Mormon Meteor II with the addition of a Curtiss Conqueror aircraft engine.

Ultimately, Ab would end up in the orange and blue Mormon Meteor III, also with that jet engine, built specifically for him.

He would go on to set—then break—record after record. Many of those records, Williams noted, have not been broken since.

“He was behind the wheel … on some occasions for 24 hours,” Jenkins II said.

At one point, Ab drove the Mormon Meteor III more than 3,200 miles continuously, except for pit stops, at a speed Williams recalled as averaging about 171 mph, setting the 24-hour speed record which Williams said would take 50 years. and a whole team of Corvettes on a different track to finally break.

Jenkins II said his grandfather still raced and broke nearly two dozen records while mayor of Salt Lake City.

Ab continued to compete and set records until his death in 1956 at the age of 73.

The Mormon Meteor III was on display for years at the Utah Capitol, painted cream and white, which Williams explained was due to a sponsorship from a motor oil company.

The Mormon Meteor III is on display at the Utah Capitol (Courtesy: Paul Christensen)

But over time, Williams and Jenkins II explained that graffiti and vandalism caused the car to deteriorate.

Ab’s son and Jenkins II’s father, Marv Jenkins, who also became a racer, fought to take possession of the Mormon Meteor III from the state so he could lovingly restore it.

“My dad adored him,” Jenkins said. “In fact, my father, for the last 25 years of his life, was immersed in the car, in restoration.”

Williams recalls watching Marv and a team rebuild the engine, with great attention to detail to return the race car to its original glory.

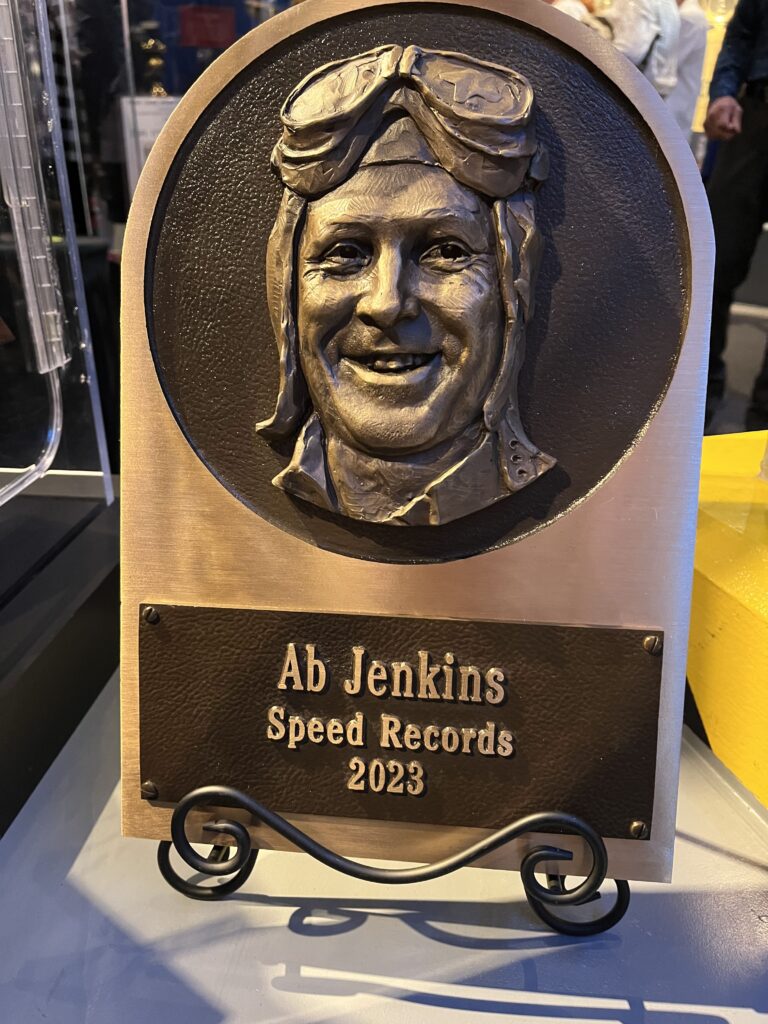

Last week, Jenkins II and two of his three brothers flew to Florida to attend two days of events for the 2023 American Motorsports Hall of Fame.

Ab was one of several people in the hall of fame class of 2023.

“I said, it’s about time,” Williams said with a smile.

Ab Jenkins Motorsports Hall of Fame Plaque (Courtesy: Ab Jenkins II)

“It was really exciting,” Jenkins II said. “We’re always excited about our grandfather and the history and so on. Dad obviously worked for years to make sure this story wasn’t lost.”

“Landspeed” Louise Noeth, well known and respected in the racing community, presented Ab’s story at the induction ceremony. He went over his history, listed his records and explained the impact he had on racing.

“This man has smashed more land speed and endurance records than any other driver anywhere,” Noeth said to applause.

Jenkins II also stood and spoke, accepting a trophy on behalf of his late grandfather.

I wasn’t sure how many people in the audience had heard of Ab Jenkins, but they certainly had a chance to understand his story that night.

“He wanted his actions and his accomplishments to speak for him, and I think that’s really what happened at Daytona,” Jenkins II said. “His actions, his achievements spoke for him. And I think he was very happy and proud of that.”

Now, nearly a century later, a Utah legacy lives on.

“He was Superman,” Williams said. “He was someone to look up to, a superhero.”

A statue of Ab Jenkins stands in front of the Mormon Meteor III at the Price Museum of Speed, while Ab Jenkins II stands behind the race car (KSL TV)